- April 12, 2023

Anubhav: Two dance forms create a unique experience

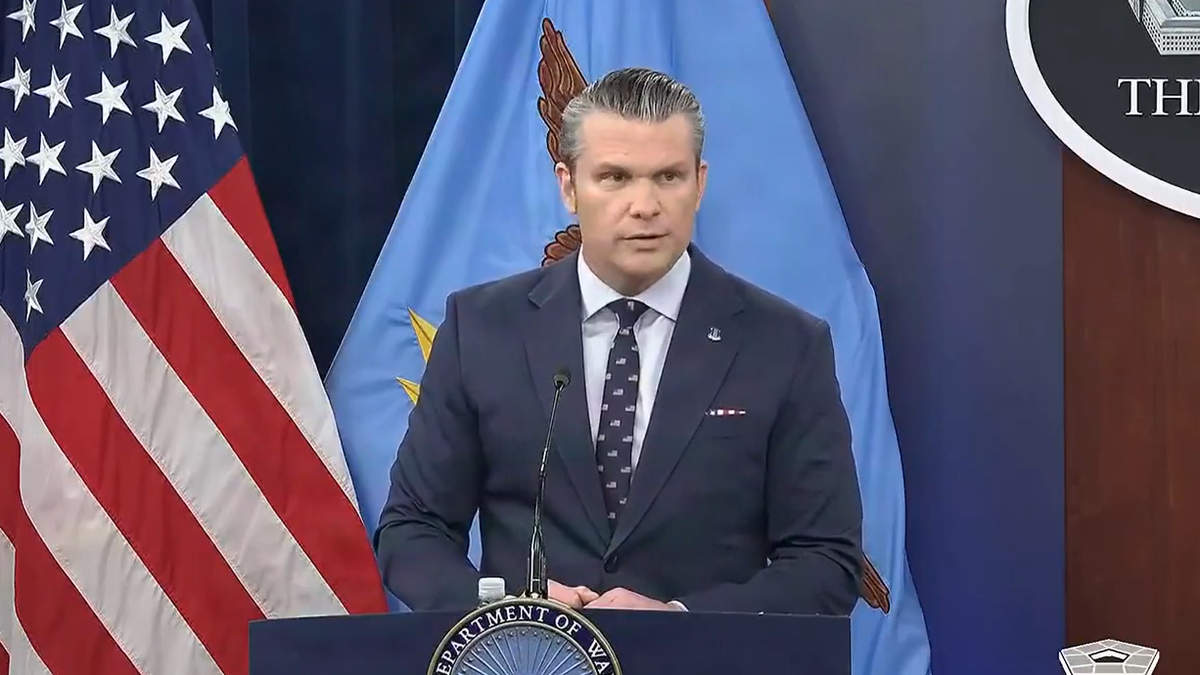

Lakshmi Parthasarathy Athreya and Shashwati Garai Ghosh

| Photo Credit: Photo courtesy: Aalaap

‘Anubhav’ was an experience — of cultural exploration, of beauty in movement, and of the joy of dancing. Presented by Aalaap at Medai, Chennai, the taglines for the show read: ‘Deeper with the senses…the deep, silent exchange of energies… this leela with dance goes on’. It was a collaboration between Bharatanatyam dancer Lakshmi Parthasarathy Athreya (disciple of Chitra Visweswaran) and Odissi dancer Shashwati Garai Ghosh (disciple of Sharmila Biswas), a high-energy celebration indeed.

While the theory of the central Marga style belonging to South-East Asia and the regional Desi styles exists, there is a corollary — the commonality between the dances of the east coast of India — ‘Anubhav’ inadvertently explored this.

Over the 75 minutes of beautiful music, the dancers bonded over the commonality of rhythm and poetry. It was a continuous flow with voiceovers smoothening the transitions — the spot-on lighting made the confluence poetic.

Rhythmic and graceful

The opening ‘Samagama’ ( choreography by Sharmila Biswas, music composition by Srijan Chatterjee) introduced the dance forms. Lakshmi began with a brisk rhythmic statement and an excerpt from a Pushpanjali, while Shashwati with a graceful piece, ‘Sthai Nato.’

Each held her own style. Lakshmi’s solo was a devotional keerthanam, ‘Anjaneya raghurama duta’ (Saveri, Adi, Swati Tirunal, dance visualisation by Chitra Visweswaran) depicting Hanuman’s strengths and virtues, with his adventures from the Sundarakandam. Lakshmi has developed a style of her own – she revels in the physicality of movement, often pushing herself to explore. Like the use of space and a wide sweep of the torso, and a deep araimandi to emphasise a point.

It goes without saying that the role of Hanuman suited the light-footed Lakshmi. There is no indulgence in her style. Her narratives were quick, matter of fact, as Hanuman made the trip to Lanka and back. There was a picture-perfect moment with the ‘Ekapadasana’ pose, symbolising Hanuman carrying the Sanjeevani mountain.

Engaging portrayal

Shashwati banked on her extensive emotive prowess, especially netra abhinaya, to explore the human side of the reviled demoness. ‘Katha Surpanakha’ (concept and choreography by Sharmila Biswas) used masks to represent every facet of Surpanakha — a woman who falls in love, a transformed seductress, a ferocious demoness, an avenging victim, etc.

In the beautiful forest, full of evocative sounds, Surpanakha is bathing in the river when she sees human footsteps. She follows them into the forest. There is a moment, suspended in time, when she sees Rama. She swoons, recollecting his ‘sundara- roopa’. She transforms into a woman with dancing eyes, hopes and dreams. She joyously follows him. Suddenly conscious, she checks herself, and tries to catch his attention. Rama responds, ‘I have a wife’ and points to his brother. Surpanakha turns to Lakshmana. This goes back and forth. The desperate Surpanakha has her nose cut off and feels betrayed. ‘Tatha kim?’ she yells, ‘What is the use?’ She removes her mask and unleashes her true violent self, promising to seek revenge on the brothers. You almost feel sorry for Surpanakha in the end.

Shashwati donned the role with ease, changing moods as the narrative flowed, perhaps not in a linear but in a circuitous, artistic way. Beautiful music, evocative rhythm and sensitive characterisation spoke of the choreographer’s and the dancer’s skills. Nothing was overtly violent or noisy, especially the angst and the violent outburst. Subtlety ruled this piece.

The dancers, closed with Jayadeva’s Ashtapadi, ‘Sakhi he’ (dance visualisation by Sharmila Biswas, music composition by Srijan Chatterjee). The switch in roles — both as Radha, Krishna and Radha, Radha and sakhi, seamlessly melted into the musical mosaic as the intense love scene unfolded. The dancers reflected the sensitivity, as they wove a web of happy chemistry, as they searched for the elusive Krishna, here, there, everywhere in a continuum.