- December 10, 2023

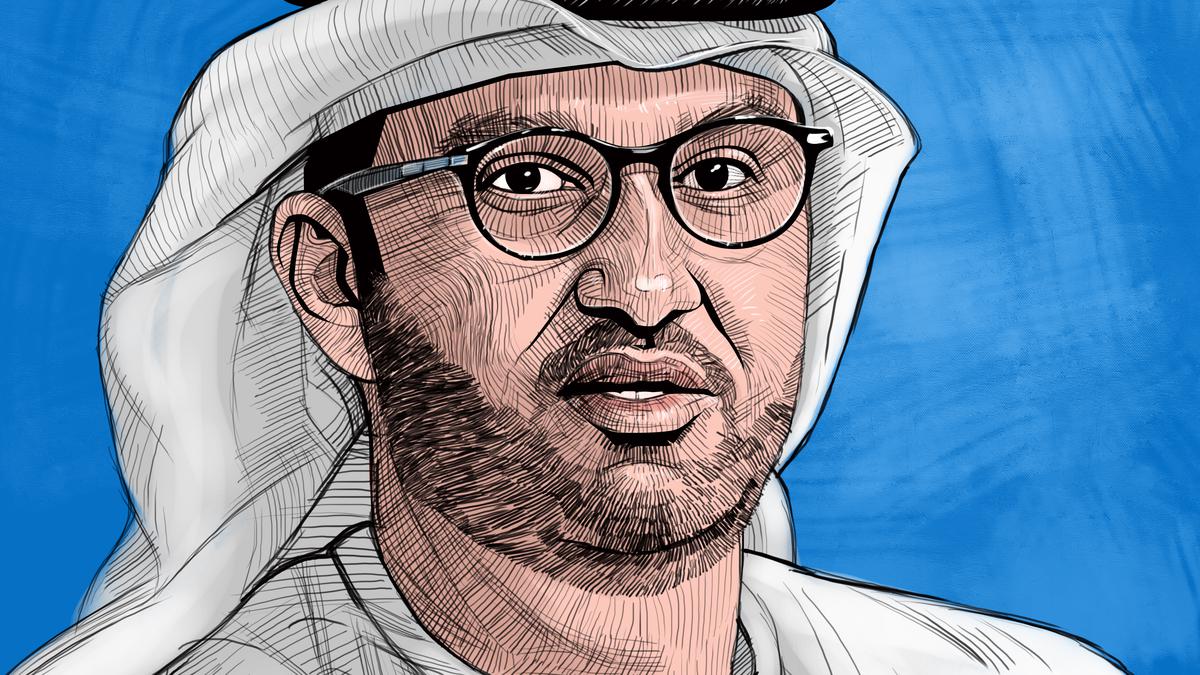

Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber | The Grand Vizier of COP28

The 28th edition of the Conference of Parties (COP) under way in Dubai is hot, flat and crowded — a Thomas Friedmanic mural of globalisation.

The hundreds of pavilions sprawled across Expo City host conferences, exhibits, food courts, stages, laser light shows all tie into the larger theme of climate change. The Grand Vizier, as an orchestrator of this confluence, is a man in his 50s. In some of the plenary meetings under way in the operatic halls, he can be seen in the centre in an elegant thawb. His beard is sharp and trimmed and his 6’3”frame lean. As the President of COP28, Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber plays the role of Persuader-in-Chief.

His role, to get the various heads of state, Ministers to meet on common ground on the greatest simmering problem that humanity faces as a collective. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that came into force in 1994 was a landmark one of sorts that, over the years, has got 194 countries to agree that the globe faces an existential threat from rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions. In the 1990s, this wasn’t yet scientific fact despite which, nations came around to acknowledging the existence of the problem.

The UNFCCC also classifies countries as ‘Annex’ and ‘Non-Annex,’ where the latter consist of the bulk of developing and industrialising countries who have contributed minimally to the historical store of carbon in the atmosphere. Annex countries (and there are sub-classifications within them) are expected to finance clean energy development in non-annex nations. Over the years, this arrangement has taken byzantine turns, with different coalitions forming, sometimes breaking, grand promises made, pledges broken, subtle and veiled threats of non-cooperation and with the result that greenhouse gas emissions are nowhere close to what science says they should be for a chance at keeping temperatures below the levels necessary to avoid cataclysm.

What has, however, stayed constant since 1995 are the annual COP meetings where ministerial delegations congregate and spend close to two weeks, trying to iron out an agreement that moves the world, by inches, towards meeting the goals of the UNFCCC. Ahead of the year’s COP, a team from the UN Secretariat assesses the logistical and technical suitability of a country to host one. Once done, a President is chosen. Like the Speaker of India’s Parliament, the President is expected to be neutral.

At COPs, the President ensures the observance of rules of procedure and works with country delegations to reach consensus on key issues. Before being designated as President, the chosen one spends nearly a year as the ‘President-designate,’ during which time they work at raising ambition to tackle climate change internationally. The Presidency works to develop effective international relationships with countries, institutions, businesses and stakeholders to achieve the necessary commitments in advance of and at COP.

Best possible outcome

The role also includes developing a vision for the best possible outcome of the meeting. Though Presidents are not obliged to recuse themselves when matters involving their countries emerge, the onus of maintaining neutrality and rising above national constraints — in the service of the greater UNFCCC good — is expected. It was this key balance that appeared off-kilter in the case of Sultan Al Jaber.

His position as the Chief Executive Officer of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), one of the largest oil companies globally, implied, the criticism went, that he could not be expected to further the elimination of fossil fuels. Rather than the gavel, he would most likely hold a flaming torch, that would give an even longer rope to the fossil fuel industry — oil and gas especially — to avoid producing and exporting these propellants that, while indispensable to the world as we know it, contributed to nearly 60% of annual emissions.

In his year as President-designate, Mr. Al Jaber, who’s also the United Arab Emirates’ Minister for industry and advanced technology, has given a few interviews. In those ones he has underlined that he sees no conflict in his role as a CEO of an oil company. Rather, this actually enabled him to involve more such industrialists, bring them to the table at COP, and have them commit to a timeline to phase out fossil fuels.

“Never in history has a COP President confronted the oil industry, let alone the fact that he’s a CEO of an oil company,” he told The Guardian. “Not having oil and gas and high-emitting industries on the same table is not the right thing to do. You need to bring them all. We need to reimagine this relationship between producers and consumers. We need this integrated approach.”

‘Zero carbon’ city

He has also sought to highlight his former leadership of another prominent renewable energy company, Masdar, in the UAE. Masdar, whose development strategy lies in buying significant stakes in renewable energy companies, boasts as its flagship project Masdar city, a ‘zero carbon’ city that is situated a few kilometres of Abu Dhabi, Mr. Al Jaber’s home city.

In the run-up to the COP meet, reports emerged that the UAE planned to use its role as host of the climate talks to facilitate oil deals with at least 15 countries. Mr. Al Jaber vociferously denied this, a day ahead of the commencement of the COP. Later, on another report, he said that he had in an online discussion raised questions about whether a fully fossil-free future was even possible, unless humanity “chose to go back to living in caves”.

He addressed this during a press conference, as President. “I am quite surprised with the constant and repeated attempts to undermine the work of the COP28 presidency.” He said his training as an engineer had taught him all his life to “respect science” and that said, for a shot at 1.5°C, all unabated coal had to be phased out and fossil fuel use “greatly reduced”.

Loss and Damage Fund

Perhaps to make up, Mr. Al Jaber, on the very first day of the COP, got countries to begin committing money to the Loss and Damage Fund, a key outcome at last year’s talks in Egypt. So far $750 million has come in that will go towards assisting countries adapt to the damage being wreaked by climate change. He even got several oil companies to become ‘net zero’, or net carbon emissions free, by 2050. He has also claimed credit for getting the United States and China, amidst their diplomatic chill, to come together and commit to a roadmap to cut methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Negotiations are nearing the final stretch with acrimony and the sabre-rattling over punctuation approaching a crescendo. Versions of the final text do seem to suggest a concerted push by developed countries to take a decisive step towards the phasing out of fossil fuels. COP history shows that momentous changes can unfurled as the last minute. If he aspires to set a legacy and make the COP the “historic” one that he claims it will be, Mr. Al Jaber must pull a rabbit out of his gavel.