- June 7, 2024

CSDS-Lokniti post-poll survey: The impact of social welfare schemes on voting behaviour

Women workers under the MGNREGS at Purulia in West Bengal.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu

Since 2004, when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government at the centre introduced a series of rights-based entitlement programmes, scholarly and popular discussions of election outcomes have highlighted the influence of social welfare policies on voting behaviour. If MNREGS was the star in 2009, it was the Ujjwala in 2019. So, what do social welfare programmes tell us about the mandate in 2024?

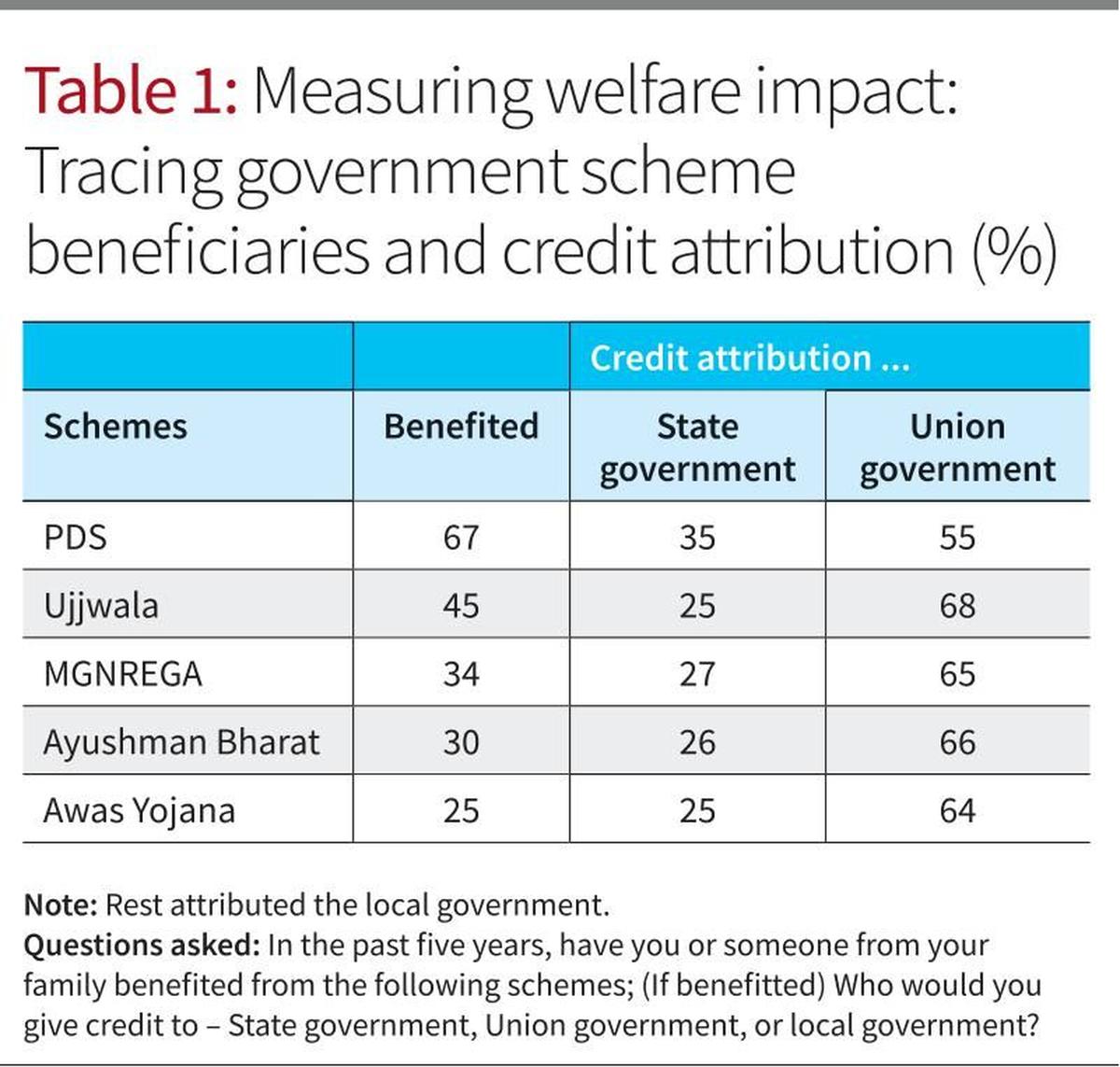

First, there is an increase in the percentage of voters who reported to have benefited from select welfare programmes. When we examine data on five major social welfare schemes, including the Public Distribution System (PDS), Ujjwala (free gas connection with cylinder), MNREGS, Ayushman Bharat (Free hospital treatment up to ₹5 lakh per family) and the housing Scheme we see that the percentage of voters who reported receiving a benefit from a scheme varied from one fourth to two thirds (25 to 67%) of the respondents (Table 1).

The increase is stark when we compare the beneficiaries from similar schemes between the last two elections. While an average of 27% of the electorate claimed to have benefited in 2019, 41% said they could take advantage in 2024 (Table 1). Whether this increase in beneficiaries is, a sign of better delivery of welfare programmes or a rise in the indigent population is something worth asking.

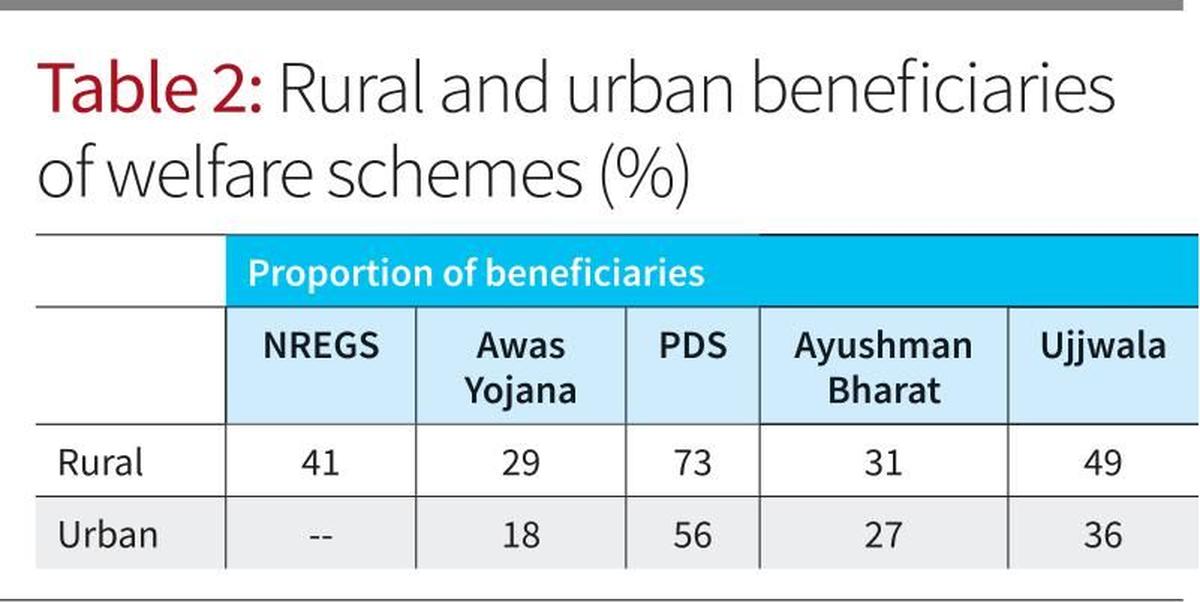

While we have no official data on the number of poor people, reports from other agencies and ground reports from the media, note that the number of people who cannot afford an adequate diet is reasonably high. It is, therefore, not surprising that the sharpest rise in beneficiaries was among those who used the PDS. While only four in every 10 (43%) of the respondents claimed to have been beneficiaries of the PDS in 2019, it went up to a whopping two-thirds (67%) in 2024 (Table 1). Furthermore, more than half (56%) of the urban and three-fourths (73%) of the rural voters claimed to have benefited from the PDS (Table 2).

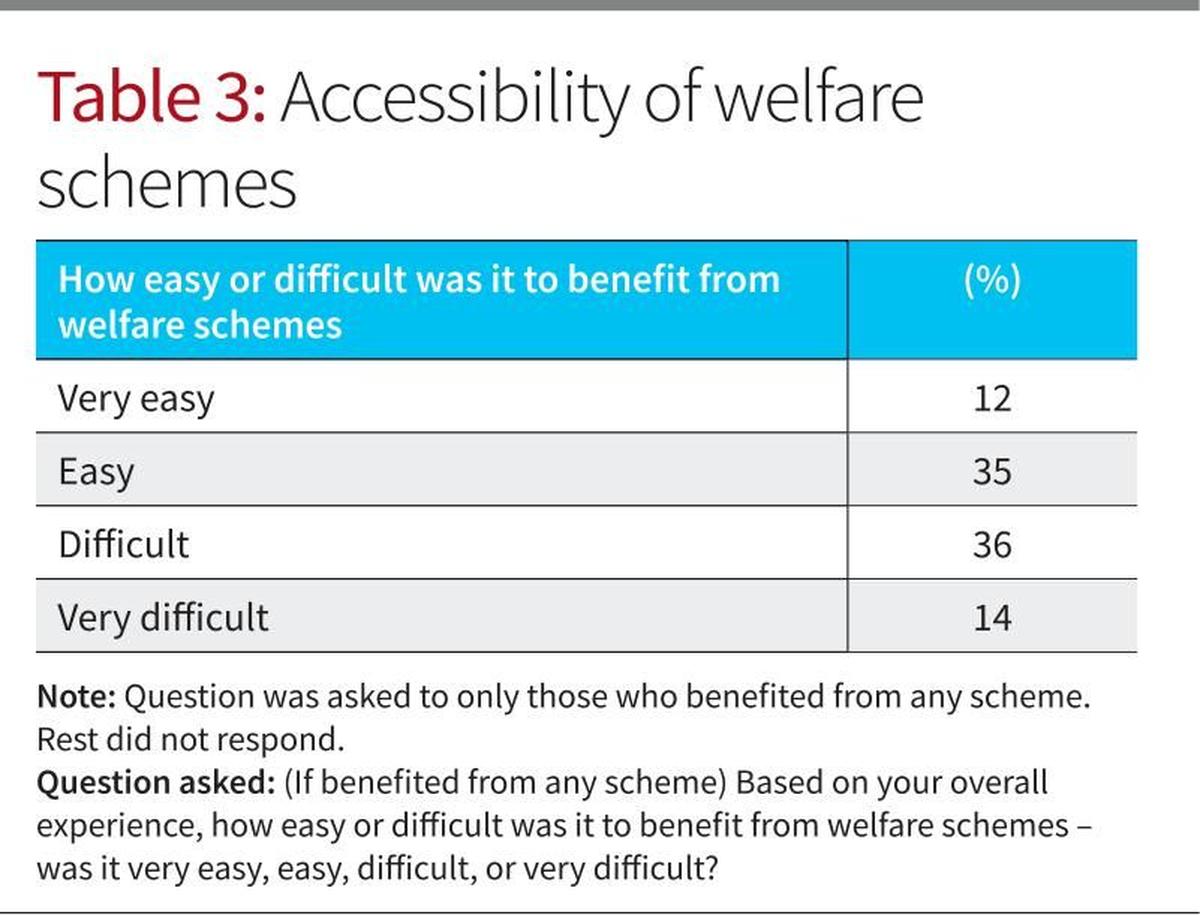

Second, despite the claims that the increased use of technology has eliminated intermediaries and reduced discretion, corruption, and leakages in welfare delivery, it appears that it has not necessarily made life easier for citizens. Nearly half the population who benefited from one of the above schemes felt that they had a difficult experience attempting to access these programmes (Table 3). However, it appears that this has not made a difference in voting.

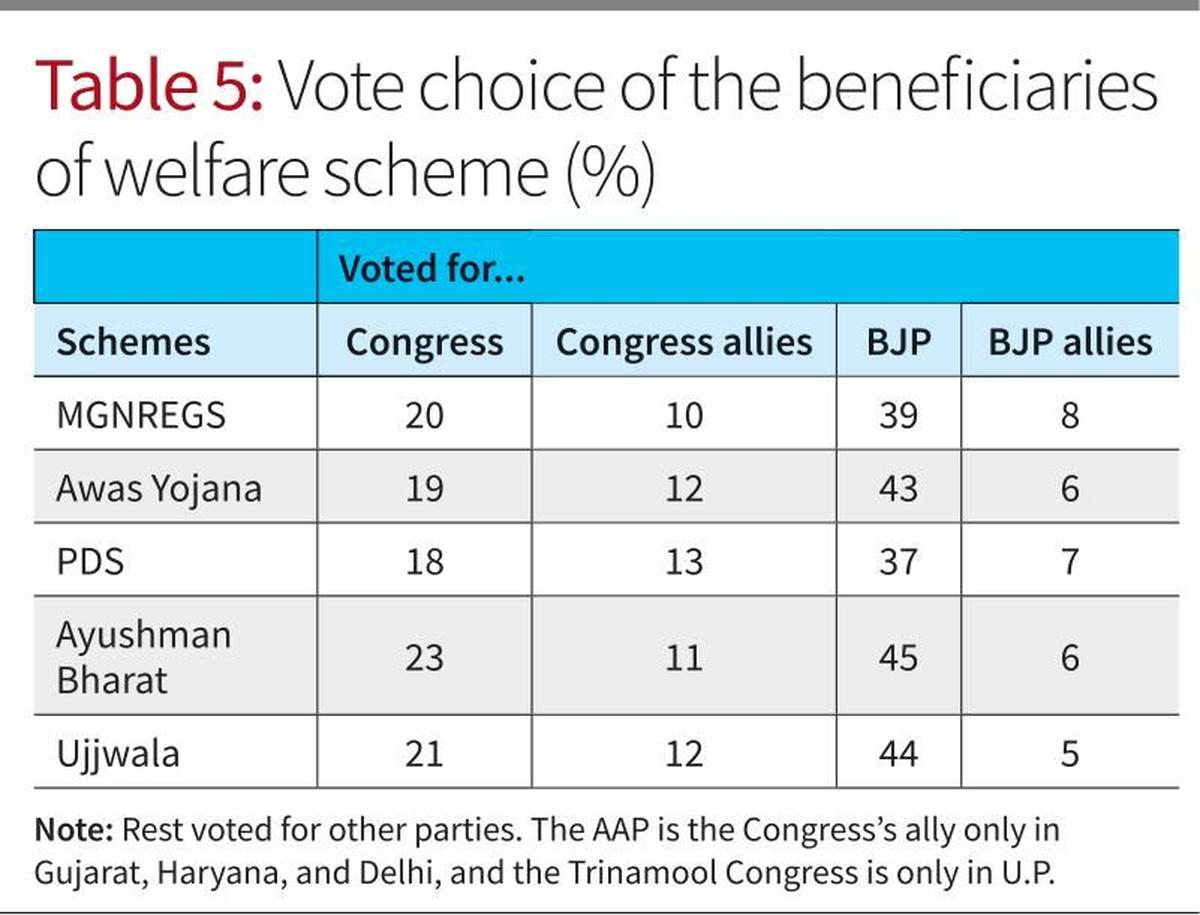

Comparative studies tell us that voters prefer the incumbent when they have benefited from the policy output or actions of the government. Data from the five schemes in 2024 suggest that beneficiaries were more likely to support the incumbent party and its allies than the opposition parties. Every second voter who benefited from a scheme supported the BJP or its allies in 2024.

Third, does aggressive branding and advertising of the welfare schemes help bring in votes? We cannot answer this, but it appears that it allows voters to assign credit. The likelihood that voters will give credit to the central government (as opposed to State or local governments) for welfare schemes has increased since 2019. While on average, four in every 10 (42%) of the respondents credited the central government for the delivery of welfare programmes in 2019, close to two-thirds (64%) of the respondents credited the centre in 2024 (Table 1).

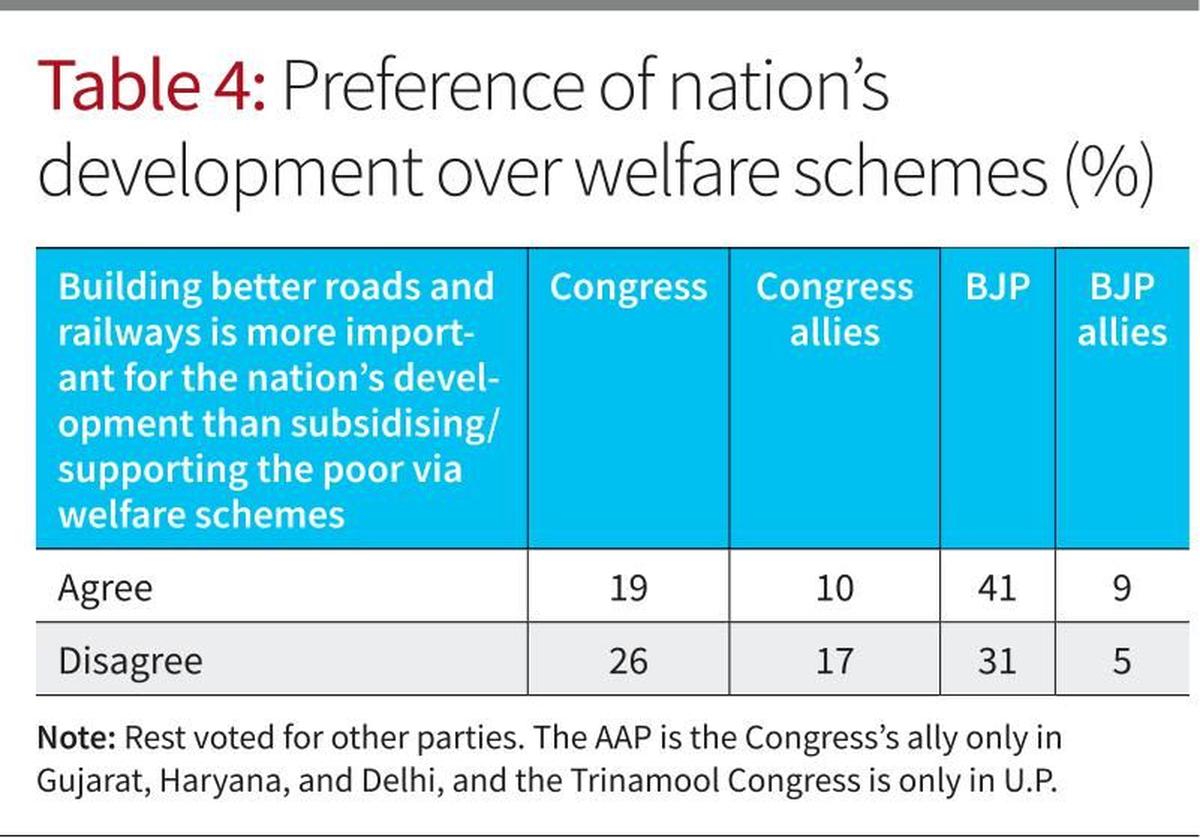

Fourth, we find that there appears to be a sharp difference in the development vision between the Congress and BJP voters. A voter who believes that the national development policy should prioritise infrastructural development over public assistance programmes is twice as likely to vote for the BJP as compared to Congress (Table 4). In a country with a large number of poor people and where welfare provisioning is understood to be an integral element of both the meaning and practice of democracy, it appears that the BJP has been constrained to embrace an alternate path. And like other parties, it has used welfare policies to attract and maintain support.

At the same time, it must be noted that the incentive for parties to focus on welfare increased with the internationally accepted supposedly more efficient welfare provisioning and delivery mechanisms. Traditionally, besides safety nets, governments invested in sectors like health and education in the name of welfare services. However, the outcomes of these investments took time, were not visible and made credit claiming difficult. The tangible and brandable problems appeared to be solved when welfare provisioning moved towards cash subsidies and direct transfers.

The benefits of welfare schemes are probably one of the many reasons influencing vote decisions, and it may be that perceptions about governance, leadership or the economy matter more. Nevertheless, the voter does not appear to have any sentimental attachment to a party that inaugurates a welfare scheme. There is more than a ten-point gap in all welfare schemes between credit attribution to the centre and votes for the BJP and its allies (Table 1 and 5). Branding may lead to credit attribution but does not probably translate into votes.

K.K. Kailash is with the Department of Political Science, University of Hyderabad.