- February 15, 2026

Found in translation

When Parliament is in session, nearly 100 people file into soundproof booths overlooking the chamber of the House. These people, ranging from young graduates to retired government employees, have quite the mandate: relaying the proceedings of both Houses into 23 different languages, spanning most of India’s official languages, as well as Sanskrit.

Simultaneous interpretation is an exacting art — it requires listening to a speaker and translating their words in real time into another language. The process is so mentally taxing that interpreters swap spots every 30 minutes. The word order in most sentences is different in English from most Indian languages, forcing interpreters to rattle off sentences quickly, skip some phrases, and do it all while listening for the next sentence.

When Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman delivered the Union Budget speech in English earlier in February, there were two ways of listening in: for MPs and those in the public gallery, a pair of headphones and a dial allowed them to tune into the translation in Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, and 20 other Indian languages; for those not in Parliament, there were live feeds on YouTube.

Vineeth (name changed) takes turns with three colleagues to translate Lok Sabha conversations in real time from English to a south Indian language. A humanities college graduate and politics buff, Vineeth looked up the Lok Sabha’s website at just the time in 2023 when the Lower House of Parliament was advertising for vacancies in a role that foreshadowed an overhaul in how Parliament did interpretations: all languages, all at once.

The job requires speed, presence of mind, and the ability to focus on two activities at the same time. It is especially challenging with sentence structure. For instance, in English, the subject-verb-object sees the most common usage, while in Hindi it is the subject-object-verb.

Now in 23 languages

The demand for simultaneous translation was raised the first time within the first week of the first session of Parliament, on May 19, 1952. A member from Andhra Pradesh asked then Speaker Ganesh Mavalankar if translations would be provided of speeches made in a language other than English and Hindi, show Parliament’s records.

Mavalankar scoffed at the suggestion. “Let us not raise imaginary difficulties,” he said, only to hastily add, “There may be genuine cases… in those cases the practice will be that the member who wishes to speak will give his own version and we shall also have to see and get it verified from some good source conversant with that language.” This is a form of consecutive translation. But ordinarily, Mavalankar hoped, members would speak in a language everyone in the House would understand. English continued to be the predominant language spoken on the floor.

During the five sessions of the provisional Parliament (January 1950–May 1952), Hindi was spoken for just 146 minutes. By the 1960s, there were more Hindi speakers in both Houses and the lingua franca was slowly changing. By 1963, the work towards setting up simultaneous translation facilities began.

In the decades thereafter, other languages faced a hurdle: interpreters were available for Hindi, English, Tamil, Telugu, and a couple of other languages, but MPs were required to inform the Speaker a day in advance, in writing, that they planned to speak in their own language. The Secretariat would then be able to ensure that an interpreter was available. Since 2023, it has become more and more common for MPs to speak in their own language, with real-time translations available for everyone else.

“The MPs are very happy,” Vineeth says, of the elected representatives who can now count on hearing proceedings in their own language all day long. “They visited us in the booth in the first few days and encouraged us.” At a closed parliamentary committee hearing, where interpreters are also stationed, Vineeth recalls, “An MP came to me and said, ‘You’ve improved a lot!’”

During a debate on the ‘Viksit Bharat’ – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) (VB–G RAM G) Bill, 2025, many MPs from Vineeth’s State spoke in their own language, since rural employment was electorally important.

Many Indians speak at least two languages fairly well. Yet, simultaneous interpretation as a profession has been rarely relied upon outside Parliament, which is among the most prestigious positions, in terms of jobs. Vineeth recalls an “oration” test and an interpretation drill as a part of his initial evaluation, followed by nearly five weeks of training on recorded speeches.

Parliament does not make recordings of interpretations available on demand. The live feeds are taken down as soon as the House is adjourned for the day. A review of some feeds during the Budget Session show it is not unusual for interpreters to stumble, and the Lok Sabha Secretariat says in a disclaimer that the service is provided for the sake of convenience only.

On the job

Ram Kesarwani, a veteran of India’s simultaneous interpretation industry, says that the “pool” of interpreters working nationwide is just in the 100s. Kesarwani’s firm, Translation India, has been doing simultaneous interpretations since 2004. He says demand has always been limited to large events with the budget to hire them.

Kesarwani says that over half the contractual interpreters in Parliament — added in the last two years to provide interpretations into almost all of India’s official languages — have worked with his firm, or been directly trained by him.

“Since 2014, the business has gone up like anything, growing five- or six-fold,” Kesarwani says. “In 2004, when I started, I realised that even the equipment and foreign language interpreters were not available in India. Indian language interpreters were also not available because only Parliament had interpreters,” he says. “So if there was any need of simultaneous interpretation in any conference, meeting, or seminar, a request was put in to Parliament for their employees. Sometimes to the different universities for foreign languages.”

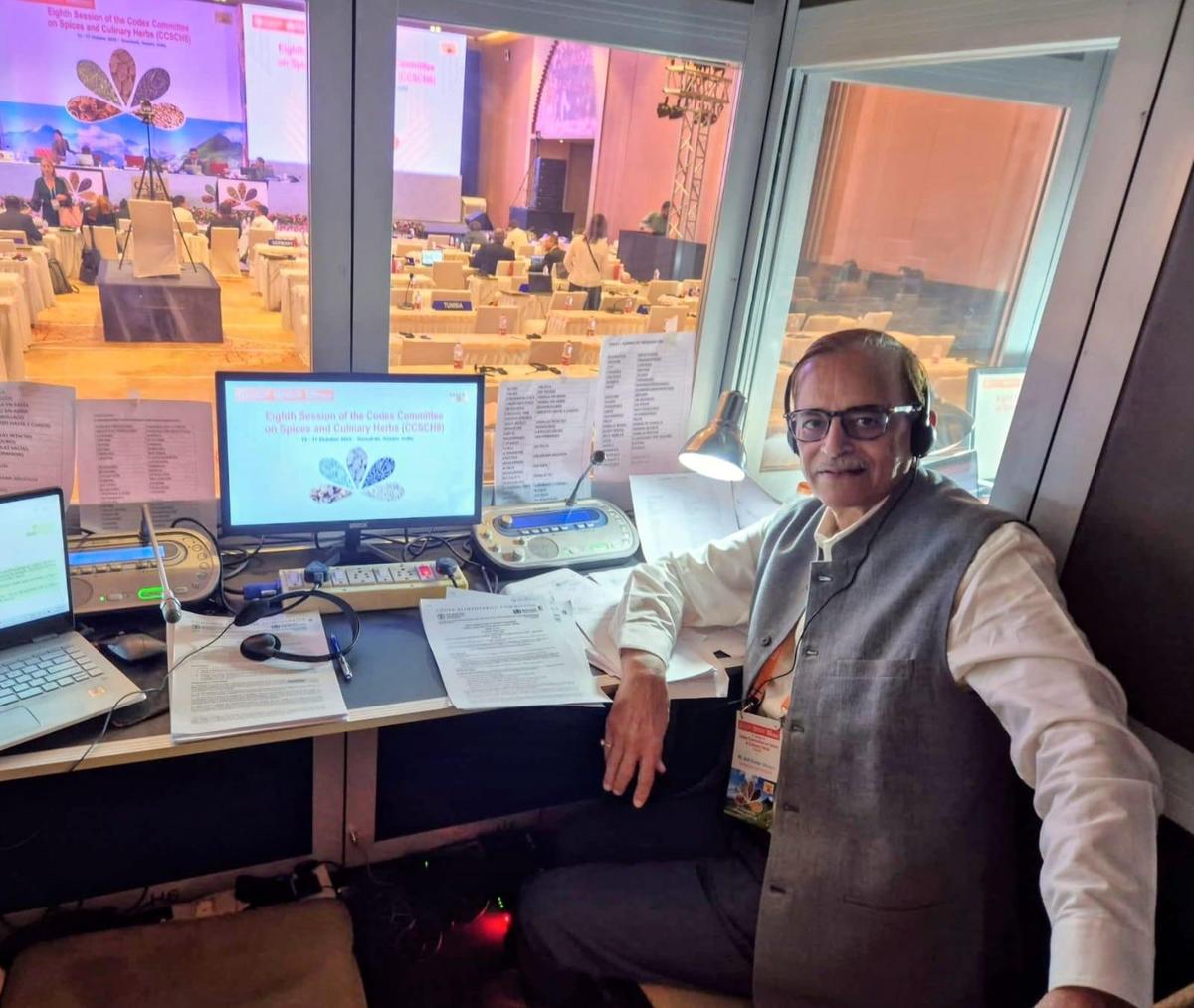

Ram Kesarwani, the founder of Translation India. File photo: Special Arrangement

When Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin convened a meeting with the CMs of Kerala, Karnataka, Punjab, and Telangana in Chennai, Kesarwani’s freelance interpreters relayed each speaker’s remarks into the respective Chief Minister’s languages, held in a hotel conference room.

Even as the simultaneous interpretation industry has seen a relative boom, he says it remains a challenging space to work in, as gigs can be hard to come by, and demand is seasonal. It spikes from October to February, when the weather is conducive for large conferences. “It doesn’t make for a secure career,” Kesarwani says.

While Parliament has permanent interpreters who draw salaries with benefits, most interpreters working there today were hired contractually, and are paid when the Houses are in session.

The pay per day in Parliament, for a contractual worker, is about ₹6,000. For conferences it can range between ₹15,000 and ₹35,000, with most events falling somewhere in between.

The pool of interpreters also includes a better-paid cohort — international language interpreters, translating for Prime Ministers and multilateral conferences. At a small gathering of interpreters in south Delhi earlier this week, some of the most seasoned participants in this ecosystem spoke about why the industry has stayed small.

A paucity and a push

Simultaneous interpretation within Indian languages is an emerging field. It has been around for a bit longer for international languages, though. “The Ministry of External Affairs used to have a dedicated cadre of interpreters,” says Anil Dhingra, a retired Spanish professor and simultaneous interpreter, who got his break with the Indian embassy in Madrid in 1975 when he was studying there, and has had the opportunity to work on many bilateral and multilateral events since. “Now they’ve stopped recruiting people in that cadre, and train Indian Foreign Service officers instead, in a foreign language abroad.” Now, he says, the MEA maintains an approved panel of interpreters who can be called on for foreign languages. In a post-World-War-II era, simultaneous interpretation became a necessity, with the establishment of a diplomatic community, as more and more nations got independence from colonial rule. The setting up of the United Nations and a multi-linguistic international landscape also emerged. The Nuremberg Trials, to prosecute Nazi war crimes, saw a particular need for simultaneous interpretation.

Anil Dhingra. File photo: Special Arrangement.

Dhingra feels the Indian government didn’t pay much attention to interpreters within India. “For the Non-Aligned Movement Summit in 1983, they got the entire team of simultaneous conference interpreters from abroad, through a British agency.” He concedes that India didn’t have the number of interpreters needed for an event at such a scale then, but that there should have been efforts to get Indian interpreters to apprentice with established professionals. He says there are still no courses that offer training in simultaneous interpretation in Indian languages.

In spite of these constraints, the interpretation pool has been “gradually” growing, says Prachi Chawla, a French-English interpreter. “There’s new demand for Hindi-Gujarati and other such Indian language pairs,” she said, citing LinkedIn job openings circulated among interpreters.

AI’s entry

People had one more way of listening to Sitharaman’s Budget speech logging into a free-to-air news channel’s regional language feeds on YouTube, where the Bengaluru start-up Sarvam AI was dubbing the speech in Sitharaman’s own voice into Hindi and other languages. The firm was using its latest translation model for Indian languages. This was the first AI-powered interpretation of Parliamentary proceedings.

The broadcast was delayed by two minutes, giving the start-up enough time to punctuate Sitharaman’s sentences, and for the translation model to generate translations that wouldn’t run on longer than her original remarks.

Machine translation is getting better in Indian languages, driven by government efforts like the National Language Translation Mission (BHASHINI) and private efforts by firms like Sarvam.

Kesarwani claims some recordings of Parliament’s consultant interpreters were being used to improve BHASHINI. Translation models get better, after all, when they have more data. The lack of online texts in Indian languages is a major reason why Indian language translation quality lags behind entrenched languages with online users, like European or East Asian tongues.

The AI wave has led to firms like Sarvam receiving unprecedented support in developing large language models (LLMs) and translation models that surpass their predecessors. Kesarwani says that machine translations for Indian languages are getting better quickly. “I think in the coming one or two years it will be perfectly alright.” He too has started providing AI-enabled services as a part of his suite of offerings. At a party of simultaneous interpreters, a fellow guest chides him for doing this.

At the party, there is music, and many professionals say that other types of skills that require coordinated movement, like playing the piano, coincide with an interpreter’s skill on the job.

Kesarwani has been doing this for 35 years now, and says those who built their careers on interpretation did so with international languages. “They are close to retiring, and new graduates haven’t come into interpretation in a big way.”

For the time being, Parliament will need real-life interpreters, as would large events, but AI is poised to find a place in the interpretation industry, he is sure.

With inputs from Sobhana K. Nair

aroon.deep@thehindu.co.in

Edited by Sunalini Mathew